What do we learn from ‘doubting’ Thomas?

In 2013 nosotros moved to our current home, which was built in 1850 every bit a square farmhouse in what was then part of a rural hamlet outside Nottingham. Ane of the changes we made quite soon after moving in was to restore the celebrated kitchen garden, which had been planted over for the previous 20 or 30 years with copse and shrubs. The soil in the area is heavy clay, and in one flower bed information technology feels as though you can actually dig up red lumps and start making a pot straight abroad! Merely I have had no trouble growing all manner of fruit and vegetables in the kitchen garden, since the area had cows and horses on it for a hundred years, and they have clearly fabricated their contribution! In addition, there was an enormous well-rotted compost heap, and earthworks it out gave the whole area a three- or four-inch covering. It is very fertile ground.

In 2013 nosotros moved to our current home, which was built in 1850 every bit a square farmhouse in what was then part of a rural hamlet outside Nottingham. Ane of the changes we made quite soon after moving in was to restore the celebrated kitchen garden, which had been planted over for the previous 20 or 30 years with copse and shrubs. The soil in the area is heavy clay, and in one flower bed information technology feels as though you can actually dig up red lumps and start making a pot straight abroad! Merely I have had no trouble growing all manner of fruit and vegetables in the kitchen garden, since the area had cows and horses on it for a hundred years, and they have clearly fabricated their contribution! In addition, there was an enormous well-rotted compost heap, and earthworks it out gave the whole area a three- or four-inch covering. It is very fertile ground.

It feels every bit though this Sunday'southward lectionary reading, John 20.19-31, is similarly rich, fertile and multi-layered, the historical base of operations overlaid with the writer'south reflections on the theological importance of what happened. Any number of theological reflections volition chop-chop grow upward in this fertile ground—and hopefully bear fruit.

At that place seem to exist two major changes of gear in this passage from what has gone before. The showtime relates to time: in the outset function of the chapter, narrative time slows down so much that we are told who is running to the tomb fastest, and who enters in first, followed by the poignant account of Mary's encounter with Jesus. Hither yous can nearly count the passing seconds; information technology is all marked past the slowness and stillness of the early on morn. By contrast, the 2d one-half of the chapter appears to be highly compressed, with a summary of Jesus' giving of the Spirit and commissioning the disciples, and a week skipping by in a moment. It is, again, worth noting that this corresponds very well with the way that nosotros remember of import experiences; the key moments are often slowed downwards in our retentivity, and details remain brilliant, long after nosotros take forgotten other details, maybe even including what would otherwise exist of import details of chronology. (I can remember the color of the car I was following on my bike as a teenager when it crashed head-on with i coming the other manner; I tin can run into the glass showering beyond the road and the racket, but I am blowed if I tin tell yous the calendar month or even (reliably) the twelvemonth.)

The second change of gear relates to the symbolic and theological meaning of this section. In the preceding passage, the typical symbolic double-pregnant of much of the Quaternary Gospel has fallen abroad. Where Nicodemus' twilight of understanding matches the time of his visit to Jesus in John 3, and the bright noonday light of John four expresses the Samaritan woman's recognition of Jesus, the actions of Simon Peter and the other disciple don't appear to accept whatever such significance. The disciple's bending over to expect in the tomb simply happens because that is what is required past the depression archway of any similar first-century rock-cutting tomb, equally we know well from archaeology. The separation of thesidarion that was wrapped effectually Jesus' head from theothonia, the strips of linen wrapped around his torso (John 20.six–7), is what y'all would merely find if the body had passed through the material and left them in their identify—bold you understood how bodies were prepared for burial in the first century.

Verse nineteen begins with one of the Fourth Gospel'south customary mentions of timing, locating the encounter of the Ten (the Twelve without Judas or, on this occasion, Thomas) in the early moments of their receiving the news from Mary (John xx.xviii) and the other women. The news has not all the same sunk in; they notwithstanding remain behind locked doors for fear of theIudaioi, best translated here as 'the Jewish [or Judean] leaders', since they still believe that they were next in line for the chop, equally those whose power is threatened seek to snuff out this dangerous new movement. Some versions (like the NIV) describe the disciples every bit being 'together', merely in that location is no such discussion in the text; it is far from articulate that they are, every bit a group, whatever less fragmented than when they were scattered by the crisis of Jesus' arrest (else why would Thomas be missing?). They are, mostly, in i physical identify but (in contrast to afterwards occasions similar Pentecost) it is far from articulate that they are 'together'.

Despite the doors beingness locked, Jesus comes and stands 'in their midst', a phrase which has a curious parallel with the vision in Revelation one of the Son of Man 'in the midst' of the lamp stands (Rev 1.xiii). In this passage, Jesus is both clearly corporeal (bodily) merely in a transformed way so that he is unconstrained by the limits of the physical world, and tin can come and get as he pleases. As in the parallel business relationship in Luke 24.36, Jesus greets them and shows them his wounds; in that gospel, this everyday greeting becomes part of Luke'southward interest in the theme of the peace of the gospel. Just in the Fourth Gospel, the language of peace specifically reminds united states of america of the Concluding Supper discourse, in which Jesus offers peace in dissimilarity with the 'trouble' his disciples volition accept in the earth (John 14.27, 16.33). On saying this, he immediately shows them not his 'hands and feet' equally in Luke, but his 'hands and side'. This confirms that information technology is the aforementioned Jesus they knew before, but besides that it is these wounds that bring nearly the peace that he has promised. The springs of living h2o that Ezekiel anticipated flowing from the side of the renewed temple (Ezekiel 47.1) actually flowed from the side of Jesus (John xix.34), who is the truthful temple (John two.xix–21), in fulfilment of Jesus' own didactics (John vii.38). Joy comes to the disciples as they brainstorm to recognise who Jesus really is, and what his death and resurrection really mean.

The second of three greetings of 'Peace…' moves the meet on to its adjacent stage. Jesus has not come simply to minister to them, but to commission them to minister to others in the same mode he has ministered to them. 'As the Father has sent me, then I transport you'. There are ii dissimilar words used hither for 'transport',apostello andpemporespectively, merely there is no sense of different meaning. (The Fourth Gospel frequently uses synonyms with no differentiation of meaning, the virtually celebrated and debated example being the dissimilar words for 'love' in John 21.) Nosotros then are offered a concise 'Johannine Pentecost' equally Jesus breathes on the disciples and invites them to 'receive the Spirit'. I don't think at that place is any piece of cake way to resolve the chronological differences between this and Luke-Acts; for the possible options see Craig Keener'south extended word in his commentary on John, pp 1196–1200. Buttheologically the Quaternary Gospel says something very similar to Luke:

Christology: Every bit Jesus' breathing illustrates, Jesus is the one who dispenses the Spirit of God, a merits that thus enfolds Jesus within the Godhead (equally Max Turner has argued in relation to Luke'due south account of the ascension and Pentecost).

Missiology: their apostolic ministry building, sent to keep the piece of work that 'Jesus began to practise' (Acts one.1), tin can but be constructive when empowered by the Spirit. Luke expresses this in the close linking of the Spirit, power, and testimony both in the ministry building of Jesus and throughout Acts.

Ecclesiology: the realisation of the forgiveness that comes from Jesus' expiry and resurrection just takes identify in the context of this Spirit-filled resurrection community. Jo-Ann Bryant (Paideia commentary, p 276–vii) argues against the traditional agreement of John 20.23 equally an 'antithetical parallelism', contrasting the forgiveness of sins with their 'retention', is mistaken, not least because the word 'sins' is non repeated and the termkrateo ('retain') does not usually have such a negative connotation. A better way of understanding the second phrase is the 'grasping' or 'retaining' of someone in the customs, thus forming a constructed parallelism betwixt the forgiveness of sins and the edifice of customs: 'Whosoever'south sins you forgive they are forgiven; and whosever you keep, they are kept.' (The verbkrateo is used of Jesus' grasp of theekklesiae, the believing communities, in Rev 2.1.)

It is inside the wide context of this rich tapestry of ideas that the narrative most Thomas comes. The others greet Thomas just the aforementioned manner Mary had greeted them 'Nosotros have seen the Lord!', using exactly the aforementioned words—but the event is quite different. Thomas' response is not rational just emotional; it is total of repetition (nails/nails, put my finger/put my hand) and drama, as he demands to merely to touch but to 'thrust' (ballo) his finger and hands in the gaping wounds. What was the reason for this bitter response?

A number of years ago, I was taking an assembly in a chief school, and asking the group to name some of their heroes. Every bit each one was mentioned, I exclaimed dramatically that I had only recently seen these people—some of them on the style to schoolhouse that morning—and if but I had known I could accept brought them along or introduced them! There was growing incredulity in the group, and rightly so. But when I asked how they would feel if this had really happened—and and so how Thomas might be feeling having missed out on the encounter—a hand at the back shot up. 'I would be very angry!' It was an amazing insight into the things that hold us back from believing, and anger at what has happened to usa and the way life has turned out seems to me to be far more mutual than an actual lack of testify, even if information technology is evidential linguistic communication that we naturally reach for. (And I take e'er since chosen the Twin 'Angry Thomas' rather than 'Doubting Thomas'.)

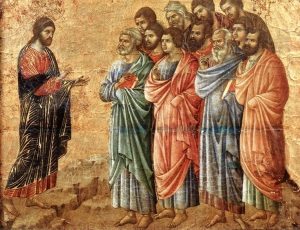

Jesus' next appearance takes place 'afterwards viii days', which perhaps, by counting the days inclusively (that is, including the first and final within the number) means 'one week afterwards' as many English translations have it. This second run across at first exactly mirrors the first: the door are locked; Jesus stands in their midst; he greets them a tertiary fourth dimension 'Peace be with you!' So his attention is turned to Thomas, with two remarkable features. Get-go, the risen Jesus completely accepts Thomas' demands of proof, and so that his invitation repeats exactly the language of finger and nails and hand and side that Thomas himself used. There is no sense in which Jesus requires belief as something contrary to or lacking in evidence. The 2d remarkable thing (contrary to this famous painting) is that at that place is no suggestion that Thomas takes him up on the offering; seeing Jesus for himself is enough, as Jesus' post-obit saying emphasises. Whatever Thomas' sin is (if that is what it be) is immediately forgiven, and he is again incorporated into the churchly customs.

Jesus' next appearance takes place 'afterwards viii days', which perhaps, by counting the days inclusively (that is, including the first and final within the number) means 'one week afterwards' as many English translations have it. This second run across at first exactly mirrors the first: the door are locked; Jesus stands in their midst; he greets them a tertiary fourth dimension 'Peace be with you!' So his attention is turned to Thomas, with two remarkable features. Get-go, the risen Jesus completely accepts Thomas' demands of proof, and so that his invitation repeats exactly the language of finger and nails and hand and side that Thomas himself used. There is no sense in which Jesus requires belief as something contrary to or lacking in evidence. The 2d remarkable thing (contrary to this famous painting) is that at that place is no suggestion that Thomas takes him up on the offering; seeing Jesus for himself is enough, as Jesus' post-obit saying emphasises. Whatever Thomas' sin is (if that is what it be) is immediately forgiven, and he is again incorporated into the churchly customs.

This and then leads into Jesus' proverb itself, and the showtime concluding statement that the writer adds at the cease of the chapter (the second last argument coming in John 21.24–25). Although in the narrative, Jesus is speaking to Thomas, in recording information technology the gospel writer is speaking to his audience, since 'those who have not seen, all the same believe' are precisely the kickoff generation of readers of this gospel—especially if it was written at the cease of the churchly era, when the get-go generation of centre-witnesses are passing abroad.

And we need to notation that those 'who accept non seen' are non in any sense inferior to those who 'have seen and believed'; it is the shared reality of belief that matters. Where Thomas had the visual show of the Living Word before him, we now have the evidence of the written word, the testimony of the beloved disciple, and both are equally sufficient evidence for placing our trust in Jesus. In reflecting on our relationship to Thomas, we might want to borrow the language of the following chapter. 'Never mind about what I want for him—what matters is that you follow me.'

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media, possibly using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would you considerdonating £1.20 a month to back up the production of this blog?

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance footing. If you have valued this post, yous tin make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the postal service, and share in respectful debate, tin can add real value. Seek first to understand, then to exist understood. Make the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to larn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; accost the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/what-do-we-learn-from-doubting-thomas/

0 Response to "What do we learn from ‘doubting’ Thomas?"

Post a Comment