Why Whas Alchohol Made Legal Again

T he U.s.a. libertarian thinktank the Cato Institute – which incidentally offers the first respond you get to this question if you practice inquire Google – doesn't mince its words about the failure of prohibition. "National prohibition of alcohol (1920-33) – the 'noble experiment' – was undertaken to reduce law-breaking and corruption, solve social bug, reduce the tax brunt created past prisons and poorhouses, and amend health and hygiene in America. The results of that experiment clearly point that information technology was a miserable failure on all counts." For the Cato Institute, as far as prohibition is concerned, there are no half measures.

It also seeks to draw social and political lessons from this era: "The evidence affirms sound economic theory, which predicts that prohibition of mutually beneficial exchanges is doomed to failure. The lessons of prohibition remain of import today. They apply not simply to the argue over the war on drugs only besides to the mounting efforts to drastically reduce access to alcohol and tobacco and to such issues every bit censorship and bans on insider trading, abortion and gambling." Market manipulation for social ends is a recipe for disaster – or so the libertarians would accept us believe.

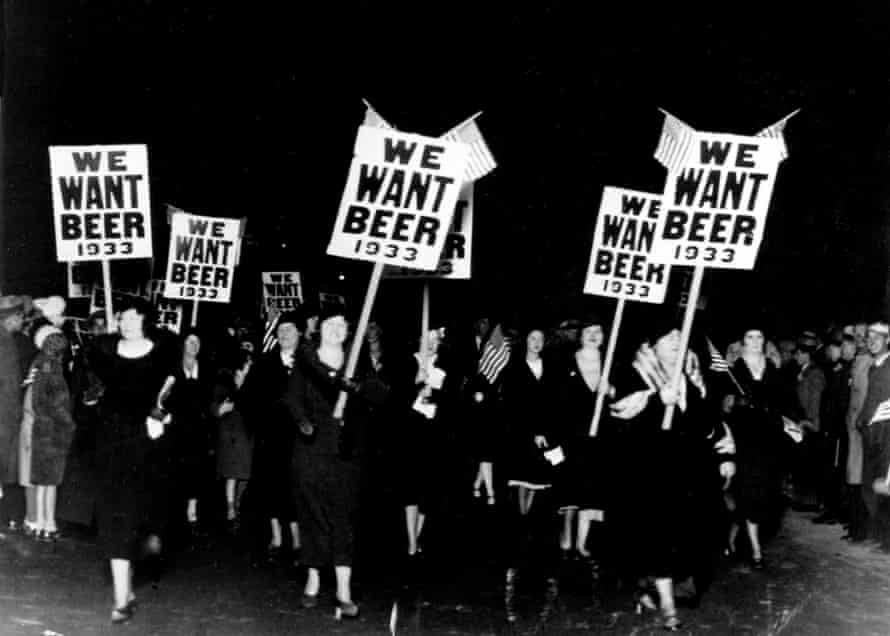

The constitute is of course right to say that prohibition failed. The 18th amendment to the Usa constitution passed in 1919 – which paved the mode for the ban, a year later, on "the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States" – was repealed in 1933 by the 21st amendment, in effect cancelling out the 18th: the merely constitutional amendment in US history e'er rescinded. This was both success – in getting the constitution amended in the first place – and ultimate failure on a colossal scale.

Yet, those who debate that prohibition was doomed from the outset – the victim of some immutable economic police force – fall into the classic historical trap of using hindsight to judge a historical phenomenon. This understates the ability of the temperance movement in the U.s.a., edifice on a century of campaigning against drink and its antisocial effects; the forcefulness of feeling in individual states, some of which had already alleged themselves "dry" before prohibition was introduced nationally in 1920; and the standing support for prohibition in the 1920s.

As the temperance historian Jack Blocker has pointed out, in the 1928 presidential contest the "dry" candidate, Herbert Hoover, was able to see off his "wet" rival Al Smith – this at the height of the and so-called jazz age, with its reputation for out-and-out hedonism. Prohibition was not quite as doomed – or as lunatic – as some critics similar to suggest. It needs to exist understood historically, non merely dismissed as an abnormality.

The central to understanding the strength of the temperance movement in the Us at the plough of the 20th century was the sheer awfulness of saloons. It was no coincidence that the organisation that coordinated the assault on alcohol was called the Anti-Saloon League. Saloons were synonymous with drunkenness, gambling, prostitution, drugs and political corruption – politicians used them as places to in outcome buy votes past offering jobs and other inducements. It was not and so much drink that campaigners wanted to eliminate as these dens of iniquity.

Loathing of saloon civilization was part of a generalised fright of social disintegration: the United states was speedily industrialising and urbanising; immigration was creating ghettoes in US cities, which were seen every bit potentially incendiary; labour militancy was increasing, as were African-American protests; socialist and agitator agitation fanned the flames of urban discontent – and made rural, Protestant America fright for its country and its moral values.

The battle over prohibition was in many respects a fight between 2 Americas – old and new, rural and urban, Protestant and Catholic, rich and poor, established and immigrant – and in the stop the emerging, urban ethos encapsulated in President Roosevelt's New Deal won. Prohibition was a staging post on the route to a new America, but old America did not requite upwards without a struggle.

The strength of anti-saloon feeling – you lot practise not go an subpoena to the US constitution passed on a whim – gave prohibition a fighting hazard of succeeding. Even later repeal in 1933, some states chose to remain dry, and the last to yield, Mississippi, only did then in 1966. But there was a fatal flaw at the center of the Volstead Act, which put the provisions of the 18th amendment into practice. Information technology banned the manufacture, auction and distribution of booze for drinking purposes (industrial booze was exempted), simply it did not outlaw consumption. People could nevertheless drink – if they could get hold of the stuff.

And get hold of information technology they did – from the criminal bootleggers who multiplied and became rich on the proceeds of smuggling, from the individuals making "moonshine" (which sometimes proved fatal when drunk) in their bathtubs, and in the "speakeasies" that proliferated across urban America. Presidents drank, senators drank, congressmen drank, constabulary chiefs drank. Turning a blind eye to criminals such as Al Capone allowed fortunes to be congenital on bootlegging.

If y'all wanted a potable, you could get i – indeed the joke was that it was easier to go booze under prohibition than previously, when a patchwork of regulations had express where and when you could buy alcohol. Some experts have argued that the federal apparatus of enforcement was never sufficient to police such a far-reaching piece of legislation over a country as vast every bit the US.

Merely historian Lisa McGirr, in her recently published volume The War on Alcohol, says information technology was not the efficiency of enforcement that was at fault. Where the authorities wanted to act, they were effective, and proved a more intrusive presence in many Americans' lives than always before. But, she argues, enforcement had an in-congenital course bias: the war was waged primarily confronting the poor, the working class, immigrant communities, the marginalised.

That attack was most systematic in the mid-west and the south, where the Ku Klux Klan were active in pursuing bootleggers and backsliders. Merely every bit the Volstead Act represented a rearguard action by old, militant Protestant, white America, so its enforcement was conditioned past the values and social biases of the groups that had backed it. Complete prohibition was always going to exist badly hard to enforce, simply this patchy, politically motivated, socially divisive application of the act made it increasingly unpopular.

An unenforceable or corruptly enforced law is a bad law, and the Volstead Human activity was somewhen discredited. It decimated the legitimate beer, spirits and fledgling wine manufacture in the Us, but Americans who wanted to drink carried on drinking as alcohol flowed in from neighbouring countries. Estimated consumption in the 1920s dropped to half its previous level – a long way short of the teetotalism that temperance campaigners, who believed that alcohol consumption would somehow get a historical bibelot, believed was possible.

As well as boosting organised crime and political abuse, prohibition made life worse for many hardened drinkers. The tendency away from spirits towards beer was reversed during prohibition, because bootleggers made greater profits past smuggling spirits. And in that location was less remedial aid available for alcoholics because heavy drinking was seen as a moral failing rather than a disease. Alcoholics Anonymous was not formed until 1935, two years later on repeal, past which time information technology was possible to separate social drinking from habitual drinking, drinking for leisure from drinking for life.

Prohibition ultimately failed because at least half the developed population wanted to comport on drinking, policing of the Volstead Act was riddled with contradictions, biases and corruption, and the lack of a specific ban on consumption hopelessly muddied the legal waters. In truth, while there was a desire to curb the anti-social effects and moral degradation of drinking, and to strike against the forces perceived as threatening the social and political status quo, at that place was no national will to stop the human activity of drinking itself.

The police force staggered on for thirteen years – testament to the forcefulness of the forces of old America – but growing disillusionment and the coming of the Neat Depression, which meant the government urgently needed the render of liquor taxes, ensured its demise. It is now seen as something of a footnote in US history – a bizarre episode betwixt the first globe war and the Depression – just because it encapsulates a disharmonism between two visions of America, information technology deserves to be far more that.

Moreover, despite the failure of prohibition, it did alter American club – and the country's drinking habits – for e'er. The former-style saloons disappeared; drinking at dwelling house became much more frequent; drinking among women, who had previously constitute saloon culture uncongenial, indeed hostile, became more common; drinking became regularised, normalised, and somewhen an accepted part of "polite" society – by the 1950s cocktails were seen as the summit of culture in many eye-course homes.

Drunkenness had not been eliminated, merely somehow social club had come up to accept drunks. The entertainer Dean Martin even managed to build a career on pretending to exist fond to the canteen. He was so convincing that some viewers idea he was. Far from changing nothing, the era of prohibition changed everything. Consumption levels did eventually return to pre-1920 levels, merely potable was never seen – or consumed – in quite the same way once again.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/30/prohibition-google-autocomplete

0 Response to "Why Whas Alchohol Made Legal Again"

Post a Comment